With the election looming, we look at the relationship between personality and political preferences.

Economic theories used to have one massive stinker of a mistake at their core: the idea that people make rational choices with money. Thankfully, eminent psychologists pointed out that humans are far from rational in their financial decisions; now a growing body of work is showing the same for political decisions, particularly voting.

Economic theories used to have one massive stinker of a mistake at their core: the idea that people make rational choices with money. Thankfully, eminent psychologists pointed out that humans are far from rational in their financial decisions; now a growing body of work is showing the same for political decisions, particularly voting.

The BPS recently posted a round-up of psychological research on politics. You’ll find that votes are influenced by the weather, a candidate’s looks, the location of polling stations, shark attacks, and more. After reading that, if you still believe that voting is a rational behaviour well… all I’ll say is please contact me for advice on how to invest your life savings in my 100% sure-fire pyramid sales scheme.

If, however, you’re interested in learning more about our quirky biases, read on. OPP Ltd’s research was based on the 16pf personality questionnaire. We collected data from 1,212 people who filled in the 16pf just before the last General Election and also answered the question:

“How would you describe your political views? – Green, Liberal, Conservative, Left, Centre, Socialist, Revolutionary Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist, Nationalist, Religious Activist, or Other.”

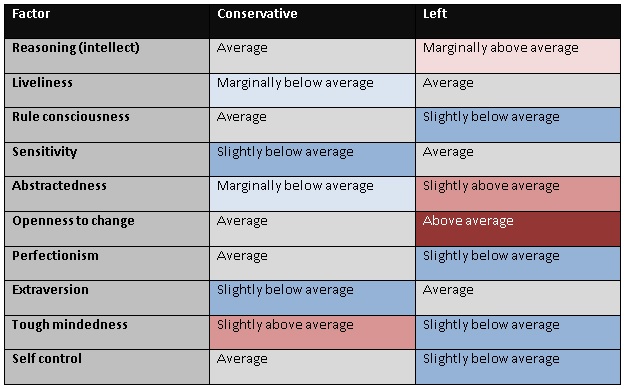

When compared with all others, people choosing “Left” were more intelligent, more tender-minded (open to change and appreciative of subjective information such as emotions), more flexible in their approach to planning and organising their lives. (108 of our group selected this option; other left views, such as “Socialist” were measured separately, effectively splitting the ‘Left’ vote into smaller, but often similar groups – for example, the 99 “Socialist” individuals have an almost identical profile to those choosing “Left”).

When compared with all others, people choosing “Conservative” (223 people in our survey) were more tough-minded: i.e. less open to emotions, tending instead to like established ideas and information presented in a more objective, factual style (note this is a preferred style – it does not imply ability to better judge if something is factually accurate). They were also more highly self-controlled (placing an emphasis on following rules, plans and conventions), and slightly less extraverted.

Unfortunately, other groups were too small to make reliable inferences from the data. Only very big differences are worth considering; for example, “Religious Activists”, although only 18 in number, showed very high levels of Self-Control (favouring rules, conventions, high standards, and self-inhibition). As for other groups, participants who identified themselves as “Feminist” buck the stereotype of strident activists – they were no more dominant than any other group, were somewhat more introverted and showed higher levels of anxiety than any other group.

Interestingly, people who said that “Other” best described their politics (356 people) showed significantly lower levels of general intelligence (getting the reasoning questions correct at a level slightly below average). It may be that interest in mainstream politics is associated with higher intellect.

As our biggest political groupings were “Left” and “Conservative”, we ran direct comparisons between the two. Here are the significant differences:

(Find out more about the different 16pf traits)

NOTE: our findings bolster a few stereotypes; but it should be remembered that there will be more variation in personalities within each political group than there is between them. Also, even though it is tempting to point to the results and show what’s wrong with different political views, none of this research says anything about which political view is ‘correct’.

Additionally, although nearly five years have passed since we gathered the data, the patterns reported here are unlikely to have varied much in the intervening time. We know that personality is stable in populations across many years, and we also see similar results to our survey, even with bigger numbers of participants and in different countries.

Surveys like this often pose more questions than they answer. We don’t have explanations for the correlations we found. For example, on the topic of intellect, although we know that more people with left-leaning politics are attracted to academic and professional roles, we don’t know if this is because they are more open minded and intellectual, if their education fosters this, or if the jobs require it (or a combination of all of these).

The next set of statistics we’re curious about are the numbers contained in the ballot boxes…